Synthetic data, Privacy and GDPR

Are you afraid that the data you share or that is collected about you will become public property? Then keep reading.

I was reading this intereting paper when I had the idea of writing this post. This is something I was already aware, but now that an official study about it came out, I got convinced I had to talk about it here.

I won’t discuss the validity of that work, I have my personal opinion on its shortcomings and hypothesis, but it still worth reading.

This post will try to vulgarize concepts that can be hard to grasp for those who are not in the field.

What is the problem?

We know that third-party entities acquire data. About us. Often times, we are promised that our data will be anonymized. But, unfortunately, this is not enough.

I report here two main reasons for this:

- the anonymization was bad, not done correctly;

- people in charge of the anonymization have no idea how good their anonymization is.

while nowadays it is easy to solve (1) and make sure to use the latest techniques, problem (2) is still an issue today.

That is, no one actually knows if the anonymized data is truly anonymous. Most companies apply techniques that are popular, they could apply them even further, but the more they do this, the less useful their collected data become. The more private your data is, the less useful it is to them. This is called the privacy-utility trade-off. They have ways to understand if the data is becoming useless, but there is no agreed way to check if the anonymized data is actually private.

Thus, there is no “Truly Anonymous Synthetic Data”.

What’s worse, is that, at the time of writing, the current GDPR regulations say NOTHING about synthetic data. They basically only restrict the original sensitive private data storage and sharing, but nothing about the fake data that is create using that original sensitive private data.

What is the current solution?

Today, as explained in Ganev et al., there are some companies that offer anonymization service, such as: Gretel, Tonic, MOSTLY AI, Hazy, Aindo, DataCebo, Syntegra, YData, Synthesized, Replica Analytics, and Statice. What they do is amazing.

These companies do more than anonymizing data: they are able to create fake data (synthetic data), that are still useful. For example, the government wants to analyze a hospital’s patient data to understand if cancer rates are going up. The hospital does not want to compromise patients’ privacy, but would like to help the government run their analysis. To do this, the hospital can create synthetic data from the original patient data, using the latest AI techniques. These synthetic data will not contain any real patient, but will still be useful to run statistcs and analysis.

Now the problem is that, while all is good in principle, no one really knows if this fake data is secure. It is not impossible that some malicious person will be able to reconstruct the original private data from the fake data.

In order to understand if such a risk exists, some companies (like the ones mentioned above) calculate some metrics on the fake data. These metrics should tell you if the fake data is useful but still private (privacy-utility trade-off). However, there is no final scientific evidence that these metrics actually work…

To calcualte these metrics, they divide the original private data into two: train data and test data. They create synthetic data using the train data only, and use the test data later to test all is good.

Let’s report them here:

-

Identical Match Share (IMS) is a privacy metric that captures the proportion of identical copies between train and synthetic records. The test passes if that proportion is smaller or equal to the one between train and test datasets.

-

Distance to Closest Records (DCR) also compares the two sets of distances. It looks at the overall distribution of the distances to the nearest neighbors or closest records.

-

Nearest Neighbor Distance Ratio (NNDR) is very similar to DCR, but the nearest neighbors’ distances are divided by the distance to the second nearest neighbor. The idea is to add further protection for outliers by computing relative rather than absolute distances.

-

Similarity Filter (SF) is similar in spirit to the privacy metrics, but rather than just measuring similarity, it excludes or filters out individual synthetic data points if they are identical or too close to train ones. Essentially, SF aims to ensure that no synthetic record is overly similar to a train one.

-

Outlier Filter (OF) focuses on the outliers; it removes synthetic records that could be considered outliers with respect to the train data.

These metrics have some drawbacks. Your fake data may have good scores under these metrics, but still be bad fake data. Or viceversa.

What else could be done?

As said, the usage of the above metrics has no scientific foundation. Companies use them because they look good. And they do look very good. But are they enough?

I had the chance myself to work on a privacy-related project, where I came across a very intersting work called MACE, and was in contact with the authors to extend their work to graph data.

This works scientifically proves that their method effectively estimates if the synthetic data are private or not, and can also calcuate a concrete value for the risk (e.g. “your fake data has a 78% risk of being de-anonymized”).

But for some reason, this new proposed technique is still being ignored. I have actually implemented it in Python. Reach out to me if interested.

Remember, when producing fake data, we divide the original private data into two: train data and test data. We create synthetic data using the train data only, and use the test data later to check all is good. The test data plays the role of representing similar data to the train one, but that is not necessarily the private data. It helps us answer the question: if I make my fake data available, and imagine that this test data is also publicly available, is it possible to predict anything about the train data, which I never shared?

To answer this question, this method checks if the synthetic data has some relationship with the train data that is not equal to the relationship it has with the test data.

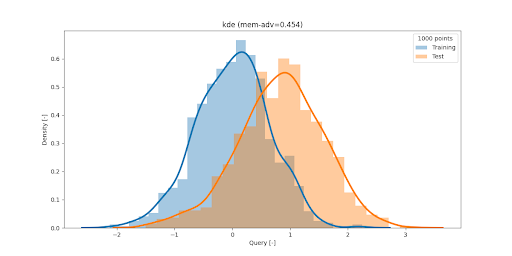

In the picture here, we see that the name query is used. This can be a broad term, that we need to define.

Imagine this fake data is now public, and imagine you are the data owner and shared it with some third-party company. Let’s re-use the hospital example above. And imagine that the test data are patient data that are publicly available (these patients shared it themselves).

Anyone could thus interact with our fake data, and this public data. They could, for example, take one public record and measure the distance from the each record in the fake data. There will be one fake record that is the closest to this public one. We do not know if it is very close, but at least one fake record will be closer that the other fake ones.

These anyones can repeat this and report this distance value for each public record. This can be the orange curve in the above Figure.

Now, they don’t have access to the train data, but you do. The question is: on average, would this distance from fake to train records be the same? More generally, would these anyones observe any difference in the reported values if they were to report values on the train data? To answer this question, you as data owner can check these values and report them. Let’s imagine that they are the blue curve in the figure above.

Are the two curves the same or different? And how different are they?

Without diving to much in the mathematics of how to come up with an exact number (e.g. 50% or 80% risk), this is how one can tell whether their synthetic fake data are private or not.

Any drawback to this?

Yes.

You need a lot of data. You need to make sure that this test data you have is sufficient to prepresent any public data that malicious people can find.

You also need to think of meaningful interactions that they can have with the fake and/or public data. Above, I reported the example of a distance, but other interactions are possible.

Conclusions

Protecting our privacy is still an open and important discussion. This post’s objective is to shed light on the matter and enable you to do now your own research about it.

It is true that current approaches have their shortcomings, but it is still the best we can do, until something better comes out.